According to all reports, Venezuela is gripped by rolling blackouts, racing inflation, homicide rates that make it the world’s second most murderous country and shortages of basic goods and medicines. The opposition parties are attempting to impeach and remove from office Nicolas Maduro, the Chavista leader, who took over from Hugo Chavez when he died in 2013 and who then managed to win narrowly the last presidential election. The opposition tactic appears to be the same as that adopted successfully in Brazil by the right-wing parties in getting Workers Party leader, Dilma Rouseff, out of the presidency.

Across South America, centre-left social democratic governments that have been in office during the great commodity price boom since the early 2000s have lost power as oil and other raw material prices plummeted due to the drop in global demand as the world economy entered its long depression after the Great Recession. Both neo-liberal and Keynesian policies adopted in Argentina, Brazil and Venezuela have miserably failed to avoid severe economic recession.

Over two years ago, I wrote on this blog that there was a significant risk that the ‘Chavista revolution’ would not survive the death of Hugo Chavez. As I pointed out then, Venezuela’s economic fortunes have always been tied to world oil prices. When petroleum prices began to fall in the mid-1980s, Venezuela’s GDP per head, a reasonable measure of average living standards, started to fall sharply from 50% above 1950 levels to just 10%. The subsequent crisis in emerging market debt that erupted in the late 1990s, as in Argentina, led to a further fall, so that living standards by the early 2000s were below that of 1950 – a great example of the success of the market economy in Venezuela before Chavez came to power!

The collapse in GDP growth coincided, not surprisingly, with a sharp fall in the profitability of Venezuelan capital (oil industry mainly). In 1989, the then president who had won with a campaign against the IMF, reversed his mandate and said that he no choice but to submit to its dictates. He announced a plan to abolish food and fuel subsidies, increase gas prices, privatize state industries and cut spending on health care and education. Profitability was driven up, but only modestly. And Venezuelan capitalism continued to fail.

When Chavez came to power, he promised broad reforms, constitutional change and nationalization of key industries under his so-called Bolivarian Revolution. Chavez’s programmes, aimed at helping the poor, included free health care, subsidised food and land reform. This succeeded in decreasing poverty levels by 30% between 1995 and 2005, mostly due to an increase in the real per capita income. Extreme poverty diminished from 32% to 19% of the population. A recent IMF report (sdn1208rev) showed, in a world of rising inequality of incomes and wealth, that there was one country that has become more equal over the last 20 years – Venezuela. And all that improvement was under the presidency of Chavez, with the gini coefficient of inequality falling from 45.4% in 2005 to 36.3% now.

But Chavez was lucky. He took power just as the commodity price boom and oil prices rose to a peak. Venezuelan capital gained with a significant rise in profitability(see graph), and because the commodity boom continued for a while longer despite the Great Recession (because China kept on growing), economic growth and profitability stayed up. Oil accounts for more than 30% of Venezuela’s GDP, approximately 90% of exports and 50% of fiscal income. With high oil prices, Chávez was able to pour money into social programmes and engage in a burst of petro-diplomacy – subsidising like-minded governments not only in Cuba but also Bolivia and Nicaragua.

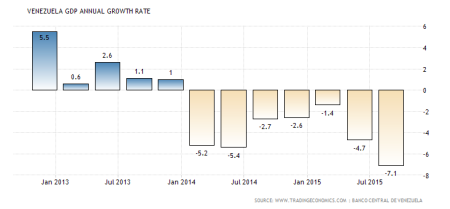

But in the last few years, the oil price has plummeted, along with other commodity prices. The world economy has slowed into a low-growth stagnation, while China, the major consumer of energy and other commodity exports, has reduced purchases dramatically. Brazil, Argentina and Venezuela have taken the biggest hits, and with that, their ‘leftist’ governments can no longer deliver for the majority.

Venezuela’s currency, the bolivar, had to be devalued in order to sustain its dollar-based oil exports. Inflation spiralled way more than in other Latin American countries.

That hit the savings of the middle-class, in particular. As a result, significant opposition to Chavismo grew, even among relatively lower middle-class strata. Government spending stopped, living standards fell (again) and social problems (especially crime) began to erupt.

Now the right-wing ‘free marketeers’ tell us that this shows ‘socialism’ does not work and there is no escape from the rigours of the market. As the right-wing Forbes magazine put it; “The ongoing disaster that is the Venezuelan economy under Bolivarian socialism tells us a number of interesting economic lessons. In part that there’s no economic theory so deluded that someone, somewhere, won’t believe in it. That we cannot simply ascribe prices randomly to goods: prices are not just an allocation method, they are information too. But the most basic point that needs to be made is that the price of something just is the price of something. We’re not going to be able to change that price simply by randomly sticking some other numbers on a piece of paper: the price of dried milk is what the price of dried milk will be, coffee will cost what coffee costs. Government, our plans, even the most deluded of economic policies, are just not going to change this: the price is the price.”

In other words, you have to do what the markets says: the price is the price. That is true only if the capitalist mode of production and the law of value dominates and is allowed to. And it did and still does in Venezuela, despite the Chavista ‘revolution’. The majority of industry and finance is still in private hands and the foreign capital still plays a powerful role. State ownership of the oil industry and its revenues are no longer enough to resist the forces of the global market. The International Monetary Fund predicts an 8 per cent economic contraction for 2016; the inflation rate is now the fastest in the world; electricity and running water are luxuries. Food and medicine are scarce.

The Chavista regime would have to move to restrict the law of value and replace the capitalist mode of production in order to end the rule of global market. That would require the state monopoly of foreign trade; expropriation of the food production and distribution; default on the foreign debt; expropriation of the banks and big businesses; and a national democratic plan of production.

Even that would not be enough if Venezuela remained isolated without any sympathetic governments in Latin America also prepared to adopt similar measures. And token support from Cuba aside,

Venezuela is isolated. China, which has loaned Caracas $65bn against future oil deliveries, is unlikely to extend fresh credit. So it is probably too late, as the forces of reaction gain ground every day in the country. It seems that we await only the decision of the army to change sides and oust the Chavistas.

No comments:

Post a Comment