The next stage in the never-ending tragedy that is the Greek economy takes place today. The Greek government meets with the EU leaders and the IMF to discuss what to do about the current ‘bailout’ programme of credit and its public sector finances.

Over the weekend, the ‘leftist’ Syriza government in Greece got through parliament yet another range of severe cuts in public spending, increased taxes and a programme of extended privatisations, in order to meet the demands of the Troika (the EU, the ECB and the IMF). In return, the Greek government will receive another tranche of funding as part of the third ‘bailout’ package designed to get Greece to repay its pubic sector debts and ‘recapitalise’ its banks.

The funds will be used partly to cover the arrears of payments to the health service and schools that the central government had run up in order to make its own books balance. But most of it will be used to pay back existing loans and interest owed to the ECB and the IMF. So more money is being borrowed from the Troika to pay the Troika in a never-ending circle of madness!

The Greek public debt burden arose for two main reasons. Greek capitalism was so weak in the 1990s and the profitability of productive investment was so low that Greek capitalists needed the Greek state to subsidise them through low taxes and exemptions and handouts to favoured Greek oligarchs. In return, Greek politicians got all the perks and tips that made them wealthy too.

This weak and corrupt Greek economy then joined the euro in 2001 and the gravy train of EU funding was made available. German and French finance came along to buy up Greek companies and allow the government to borrow and spend. The annual budget deficits and public debt rocketed under successive conservative and social democratic governments. These were financed by bond markets because German and French capital had invested in Greek businesses and bought Greek government bonds that delivered a much better interest than their own. So Greek capitalism lived off the credit-fuelled boom of the 2000s that hid its real weaknesss.

But then came the global financial crash and the Great Recession. The Eurozone headed into slump and Eurozone banks and companies got into deep trouble. Suddenly a Greek government with 120% of GDP debt and running a 15% of GDP annual deficit was no longer able to finance itself from the market and needed a ‘bailout’ from the rest of Europe.

But the bailout was not to help Greeks maintain the living standards and preserve public services during the slump. On the contrary, living standards and public services had to be cut to ensure that German and French banks got their bond money back and foreign investment in Greek industry was protected.

So through the bailout programmes, foreign capital was more or less repaid in full, with the debt burden shifted onto the books of the Greek government, the Euro institutions and the IMF – in other words, taxpayers and citizens. The Greek people were ultimately committed to meeting the costs of the reckless failure of Greek and Eurozone capital.

Last summer 2015, the ‘Greek crisis’ came to head. The newly-elected leftist Syriza government appeared to refuse to accept the austerity measures demanded by the Troika. Finance minister Yanis Varoufakis went into the lion’s den of the Eurozone group meetings to call for debt relief and a rejection of the austerity measures. Eventually, Syriza leader Tsipras called a referendum of the people to say yes or no to the terms of Troika, amid the cutting off of credit to the Greek banks by the ECB, the imminent threat of financial and economic collapse and dire threats from the German leaders and the Eurozone group. The Greek people amazingly (including Tsipras) voted by 62% to say no to these threats and austerity. The No side won every constituency in Greece and Tspiras had a mandate to reject the Eurozone demands.

But he and most of the other Syriza leaders backed down. They could not see any alternative but to accept the Troika demands. As they saw it, otherwise, credit would be cut off, Greece would be thrown out of the Eurozone and the economy would plunge even deeper into depression. They decided to agree to Troika terms in return for the vague promise that, some time later, the EU leaders would agree to ‘debt relief’. This presumably meant that Greece would have to pay less back to its creditors (now mainly the EU official loans) and so would have some ‘fiscal space’ to end austerity and get the economy going again – on a capitalist basis.

This is what I wrote last August on the news that Syriza had agreed to the terms of the third bailout: “The economic uncertainty is whether, even if the Greeks follow the deal to the letter, it will work to reduce Greece’s public sector debt burden, restore economic growth and reduce unemployment and reverse the drastic fall in living standards. The answer to that question is clear. It won’t”

“The IMF is not prepared to provide any further credit as part of this bailout because it does not think that Greek public sector debt can be stopped from rising as a share of GDP and that the Greeks can ever service it by borrowing from the market. In other words, the debt is ‘unsustainable’.”

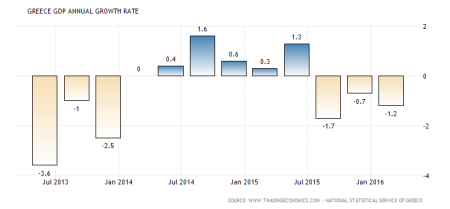

Now here we are, getting on for a year later, and Greece remains in economic recession. The Greek economy contracted 0.4 percent on the quarter in the first three months of 2016 after growing by a meager 0.1 percent in the previous period. Compared with the same period a year earlier, the non-seasonally adjusted GDP shrank for the third quarter in a row by 1.2 percent, accelerating from a 0.7 percent fall in the last three months of 2015. So, since the Syriza government backed down, Greece has fallen back again into recession.

Unemployment remains well above 20% and is double that for youth unemployment. Average real wages are still falling; pensions have been cut yet again and public services remain in tatters. And Greece is taking the brunt of the influx of refugees from Syria and the Middle East.

The Syriza government has done everything it has been asked of by the Troika in making the Greek people pay for the failure of Greek capitalism. And yet the EU leaders have still not agreed to ‘debt relief’. Indeed, they are talking of only considering it once the austerity measures in the latest bailout have been implemented in full and the programme comes to an end in 2018. In the meantime, the Greek government is supposed to run a budget surplus (before interest payments on loans) of 3.5% of GDP a year for the foreseeable future. That is a level way higher than any other country in the EU and way higher for so long than any other government has achieved ever!

No wonder the IMF considers this approach as unsustainable. The IMF executives have a mandate not to lend money to any country that it does not think can pay it back – simple. And the IMF analysts reckon that applies to Greece. (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2016/cr16130.pdf)

“Even if Greece, through a heroic effort, could temporarily reach a surplus close to 3.5% of GDP, few countries have managed to reach and sustain such high levels of primary balances for a decade or more, and it is highly unlikely that Greece can do so considering its still weak policy making institutions and projections suggesting that unemployment will remain at double digits for several decades.” IMF.

So the IMF wants the EU leaders (who own most of the debt) to agree to ‘debt relief’. The EU leaders stubbornly refuse as they think it would set a precedent for Eurozone governments to get away from ‘honouring’ their obligations and would look bad in particular to the German electorate with a general election only 18 months away and the Eurosceptic parties there gaining ground. This is an irony considering that in 1953 Germany was allowed to write off the debt it owed to the Allied Powers after the second world war. That was done to get Germany to return to the capitalist fold and allow economic recovery. But not for Greece in 2016.

Today, the IMF and the EU leaders meet with the Greek negotiators. The IMF has repeated it would take part in Greece’s €86bn bailout only if its European partners could prove “the numbers add up”.

The IMF reckons that without debt relief, Greece’s public sector debt to GDP ratio (the measure everybody follows) would not fall even with further austerity. Indeed, it would rise from around 180% now to nearly 300% by 2060 – in a ‘snowball’ effect where debt is repaid with more debt and interest payments keep rising on top.

Greece’s gross financing needs, or GFN, (the money it would need to service its debt pile) would soar to 67.4 per cent of total economic output. That compares to financing needs of just 18.5 per cent today. With sufficient ‘debt relief’, Greek public debt could finally start to fall, the IMF claims. Even so, the debt ratio would still be above 100% over 40 years from now!

And what is this ‘debt relief’. Well, the IMF suggests “payment deferrals” until 2040 – which would mean Greece would pay none of the costs of servicing any of its bonds or loans for the next 24 years. This would mean extending the grace period on its existing European Financial Stability Fund loans by another 17 years, ESM loans another 6 years, and loans owed to member states by 20 years. In total, these measures would help reduce the country’s payments bill by 4.5 per cent of GDP over the next 24 years, according to the IMF.

An additional proposal is to extend the life on the loans owed to Greece’s fellow member states (known as the Greek loan facility) by 40 years, from their current maturation date of 2040 to 2080 instead. And loans issued by the eurozone’s emergency bailout fund – the European Financial Stability Facility – would be extended by 24 years from 2056 to 2080 and from the permanent European Stability Mechanism (Greece’s largest single creditor) by another 20 years, also taking them up to 2080. Combined, the IMF calculates such measures would help keep the cost of servicing Greece’s total loans below 20 per cent of GDP by 2060.

The IMF also proposes that Greece should pay no more than 1.5 per cent of its GDP every year to service the costs of its ESM/EFSF loans until 2045. The fund proposes this be done by swapping current expensive short-term bonds with higher interest rates, with longer term paper with lower repayments.

All these ideas are not really debt relief in the sense of actually writing off the debt. Such a move is taboo. Greece must honour its ‘debts’. In reality, these proposals would mean that the debt would be perpetually ‘rolled over’ to the future and interest payments would be reduced to the minimum. The IMF wants these measures of debt relief to start now while the Euro leaders, led by Germany want to push them back to after 2018.

But even these measures of debt relief won’t work unless the Greek economy starts to grow again. How can the Greek economy be made to grow? I posed three possible economic policy solutions last summer. There is the neoliberal solution currently being demanded and imposed by the Troika. This is to keep cutting back the public sector and its costs, to keep labour incomes down and to make pensioners and others pay more. This is aimed at raising the profitability of Greek capital and with extra foreign investment, restore the economy. At the same time, it is hoped that the Eurozone economy will start to grow strongly and so help Greece, as a rising tide raises all boats. So far, this policy solution has been a signal failure. Profitability has only improved marginally and Eurozone economic growth remains dismal.

The next solution is the Keynesian one. This means boosting public spending to increase demand, cancelling part of the government debt and for Greece to leave the euro and introduce a new currency (drachma) that is devalued by as much as is necessary to make Greek industry competitive in world markets. The trouble with this solution is that it assumes Greek capital can revive with a lower currency rate and that more public spending will increase ‘demand’ without further lowering profitability.

But the profitability of capital is key to recovery under a capitalist economy. Moreover, while Greek exporters may benefit from a devalued currency, many Greek companies that earn money at home in drachma will still be faced with paying debts in euros. Many will be bankrupted. Already over 40% of Greek banks loans to industry are not being serviced. Rapidly rising inflation that will follow devaluation would only raise profitability precisely because it will eat into the real incomes of the majority as wages failed to match inflation. There would also be the loss of EU social funding and other subsidies if Greece is also ejected from the EU and its funding institutions. This solution has been rejected by the Greek government and most of its people too.

The third option is a socialist one. This recognises that Greek capitalism cannot recover to restore living standards for the majority, whether inside the euro in a Troika programme or outside with its own currency and with no Eurozone support. The socialist solution is to replace Greek capitalism with a planned economy where the Greek banks and major companies are publicly owned and controlled and the drive for profit is replaced with the drive for efficiency, investment and growth. The Greek economy is small but it is not without an educated people and many skills and some resources beyond tourism. Using its human capital in a planned and innovative way, it can grow. But being small, it will need, like all small economies, the help and cooperation of the rest of Europe.

This solution has never been posed by the Syriza leaders. So the EU leaders and the Syriza government will continue trying to meet the demands and targets of the Troika in the vain hope that European capitalism will recover and grow and so allow Greeks to get some crumbs off the table.

There may be some deal on ‘debt relief’ from the discussions. But it will still mean that Greece has an unsustainable burden of debt on its books for generations to come, while living standards fro the average Greek household fall back below where they were before Greece joined the Eurozone. And another global recession is fast approaching.

No comments:

Post a Comment