Apparently Hilary Clinton, the Democratic dynasty front- runner for the US presidency in 2016 is worried about rising inequality of income and wealth in America. She has recently consulted Joseph Stiglitz, Nobel prize winner in economics, and author of now two books on the issue of inequality.

However, don’t get your hopes up too high that a US president might take action on the extremes of wealth and poverty in America. Among the top ten contributors to her campaign are JPMorgan Chase, Goldman Sachs, CitiGroup and Morgan Stanley. As secretary of state under Obama, she pressured governments to change policies and sign deals that would benefit US corporations like General Electric, Exxon Mobil, Microsoft, and Boeing. Clinton served on WaltMarts board of directors from 1986 to 1992 and the law firm she worked for, Rose Law Firm, represented the corporation. During her three trips to India as secretary of state, she tried to convince the government to reverse its law aimed at keeping out big-box retailers like WalMart.

So anything that Stiglitz might have said will not gain any traction if Clinton becomes president in 2017. But it shows that inequality is still THE issue in the minds of the ‘liberal left’ and among mainstream ‘liberal’ economists. Both Stiglitz and Tony Atkinson have new books out on the subject, while the OECD has a new report out arguing that rising inequality is damaging economic recovery (http://www.oecd.org/social/reducing-gender-gaps-and-poor-job-quality-essential-to-tackle-growing-inequality.htm).

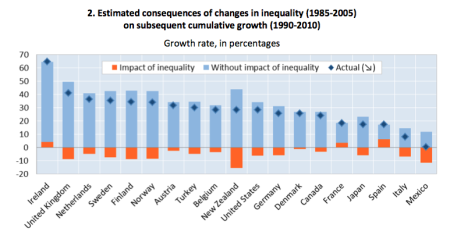

The OECD sifts through 30 years of data from its predominantly rich member countries and finds that, when the Gini coefficient, a popular measure of inequality (a Gini of 0 means everyone has exactly the same income; a Gini of 1 means one person gets all the income) goes up, growth declines. But is that because inequality hurts growth, or vice versa?

The OECD uses a statistical test to conclude it’s the former. The OECD finds that higher inequality has a significant impact on relative educational attainment among different income classes. As inequality goes up, the poorest 40% of the population get fewer skills and lower quality education.

The OECD then estimates how much more education the poor may have had if inequality had not increased and plug that into a growth model that includes components such as human capital. From this, the study concludes cumulative economic growth was 4.7 percentage points lower for the average OECD country between 1990 and 2010 (that’s about $2,500 for the average American).

So the OECD suggests that rising inequality causes slower growth because the poor get worse education for better skills at work. This is the cause that is always brought up by mainstream economics (see my post, https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2010/04/07/inequality-of-opportunity/).

That rising inequality might be a result of the concentration and centralisation of capital ownership and the application of neo-liberal policies to increase the rate of surplus value is ignored.

And yet economic inequality has reached extreme levels. From Ghana to Germany, Italy to Indonesia, the gap between rich and poor is widening. In 2013, seven out of 10 people lived in countries where economic inequality was worse than 30 years ago, and in 2014 Oxfam calculated that just 85 people owned as much wealth as the poorest half of humanity. In Even it up: time to end extreme inequality (cr-even-it-up-extreme-inequality-291014-en[1]), Oxfam reckoned that the gap between rich and poor is growing ever wider and is undermining poverty eradication. If India stopped inequality from rising, 90 million more men and women could be lifted out of extreme poverty by 2019.

Tony Atkinson is the father of modern inequality research (see my post, https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2013/07/14/the-story-of-inequality/), providing the data and evidence on inequality of incomes in the major economies well before Emmanuel Saez or economics rock star, Thomas Piketty (see

http://weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1013/unpicking-piketty/).

Atkinson’s latest book, Inequality what is to be done aims to look at what should be done to reduce inequality. (http://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674504769)

As well as diagnosing the problem of economic inequality (especially inequality of income)—showing why it matters in advanced societies (“It does matter that some people can buy tickets for space travel when others are queuing for food banks”) and how it has changed over time, Atkinson presents a series of policy proposals for doing something about it.

Rising inequality is not some inexorable long-term process in capitalism (namely a larger rate of return on wealth over the growth in national income) as Thomas Piketty has argued. Atkinson reckons rising inequality is directly the result of neo-liberal policies introduced from the late 1970s onwards. Cuts in the welfare state probably accounted for a substantial part of that [rise in the gini inequality number]. And these could be reversed.

Atkinson makes the valuable point that what matters for inequality is who controls the levers of capital. “In the old days, the mill owner owned the mill and decided what went on [there]. Today, you and I own the mill. But who decides what goes on? It’s not us. That’s the important difference. And it doesn’t really appear in Piketty’s book, which is actually more about wealth than it is about capital.”

Yes it is capital not wealth (as Piketty thinks) that matters – but is Atkinson right to think that the owners of capital have in some way relinquished control to pension funds? The owners of capital – the billionaires – still control the means of production (http://www.forbes.com/sites/bruceupbin/2011/10/22/the-147-companies-that-control-everything/) and make the decisions on wages, bonuses, shareholdings and government policy on corporate taxes and welfare benefits (see my post, https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2015/02/01/growth-inequality-and-davos/ ).

Atkinson seems to accept neoclassical welfare economics, namely that an economy will run efficiently and that any intervention like redistribution will make it less efficient, so there’s a trade-off. But he says this only applies to perfect competition whereas economies are really dominated by monopolies. “In that less perfect world, it’s not clear that there is any such trade-off.” But there is no trade-off in the world of perfect competition either because that is an imaginary construct of mainstream economics.

Atkinson calls for a living wage, guaranteed government employment for 35 hours, works councils to give people a say in their jobs; investment in technology for jobs, higher marginal income tax rates (up to 65%, he says); a wealth and inheritance tax with the revenues to be used to invest in pensions. All this sounds fine, although it does not deal with the very issue that Atkinson poses in his book, namely the control of the levers of capital. So his excellent reforms to reduce inequality will just bounce off the deaf ears of the likes of Hilary Clinton.

As I said earlier, Joseph Stiglitz apparently does have the ears of Clinton – for the moment. Stiglitz has just published his second book on inequality called The Great Divide, http://books.wwnorton.com/books/detail.aspx?id=4294987343.

In it, he stresses a range of economic and institutional changes weakening ordinary workers that serve to benefit the wealthiest in society. For example, the bonuses that Wall Street executives received in 2014 was roughly twice the total annual earnings of all Americans working full time at the federal minimum wage. Stiglitz rages at the callous ignorance of the rich: “I overheard one billionaire — who had gotten his start in life by inheriting a fortune — discuss with another the problem of lazy Americans who were trying to free ride on the rest,” Stiglitz writes. “Soon thereafter, they seamlessly transitioned into a discussion of tax shelters.”

For him, however, reducing inequality does not depend on controlling the levers of capital but on ‘more democracy’. As Stiglitz notes: “Inequality is a matter not so much of capitalism in the 20th century as of democracy in the 20th century.”

Whereas Piketty believes that extreme inequality is inherent to capitalism, Stiglitz argues that it’s a function of faulty rules and regulation. While he admires Marx’s critiques of exploitation and imperialism, he has little time for his analysis of economics. Stiglitz’s positions are essentially Keynesian and would have been viewed as fairly conventional in the pre-Thatcher and pre-Reagan era.

“My argument is that these guys – the bankers and monopoly corporations – have destroyed capitalism in some sense,” he says. “There are certain rules which are required to make a market economy work. And these guys are really undermining these rules. My book is really about trying to get markets to act like markets. That’s hardly radical, at one level. But at another level it is radical because the corporations don’t want markets to look like markets.”

Atkinson’s answer is a radical redistribution of income and wealth through tax, employment and welfare measures. Stiglitz’s solution is more regulation of the banks and monopolies by democratic governments. Don’t hold your breath waiting for a Democratic Clinton to do either or both.

for more inequality, see my Essays on Inequality

Createspace https://www.createspace.com/5078983

or Kindle version for US:

http://www.amazon.com/dp/B00RES373S

and UK

http://www.amazon.co.uk/s/?field-keywords=Essays%20on%20inequality%20%28Essays%20on%20modern%20economies%20Book%201%29&node=341677031.

No comments:

Post a Comment