After that, the major capitalist economies experienced a series of regular and recurrent slumps starting with the first simultaneous post-war international recession in 1974-5, the deep ‘double-dip’ recession of 1980-2, the industrial slump of 1990-2, the mild but global recession of 2001 and finally the Great Recession of 2008-9, the deepest and longest lasting slump since the 1930s Great Depression.

Mainstream macroeconomics did not see these recessions coming and even after they arrived, economists failed to consider their causes or even accept that what mainstream economics used to call ‘business cycles’ were back.

The Great Recession has forced the mainstream to consider causes and explanations more carefully. Keynesians continue to revive the view that slumps are due to sudden collapses in ‘effective demand’ and/or changes in ‘animal spirits’ (the psychological temper or confidence of entrepreneurs about the future). As the Great Recession has morphed into a Long Depression, where there is no recovery to previous trend growth in output, investment or incomes, Keynesian theory has dredged up the ideas of the pre-war Keynesian Alvin Hansen who proposed that the immediate post-war capitalist economies would enter ‘secular stagnation’ due to a slowdown in population growth and chronic weak demand (he was wrong).

The doyens of modern Keynesian economics, Paul Krugman and Larry Summers, now hold that the major economies (or at least the US) are in a permanent liquidity trap, where even with interest rates near zero, business investment won’t pick up enough to restore full employment (not that capitalism has ever achieved that except maybe in those few ‘golden’ years of the 1960s). This stagnation can only be broken by government intervention and/or investment.

The still dominant neoclassical school of economics denies that such stagnation exists or is endogenous to the capitalist economic system. For this school, the Great Recession was a particularly large ‘shock’ to an otherwise steady development of output, investment and employment. But it was temporary – Ben Bernanke in his new blog is determined to provide the reasons why it is temporary (see my post, https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2015/03/30/ben-bernanke-and-the-natural-rate-of-return/). These economists reckon the issue is due to either bad monetary policy (Bernanke) or the lack of control over banks and credit, causing financial crises (Rogoff, https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2013/04/24/the-two-rrs-and-the-weak-recovery/) – not a problem of the lack of demand or ‘secular stagnation’. So the answer is not more government investment and government borrowing but financial stability and solid monetary policy.

As Brad de Long put it in a recent post (http://equitablegrowth.org/2015/05/01/project-syndicate-even-dismal-science/), “Summers and Krugman now believe that more expansionary fiscal policies could accomplish a great deal of good. In contrast, Rogoff still believes that attempting to cure an overhang of bad underwater private debt via issuing mountains of government debt currently judged safe is too dangerous–for when the private debt was issued it too was regarded as safe.”

The concept of the nature of modern capitalist economies as ones that have an equilibrium growth path that sometimes is knocked off kilter by random events and then returns to equilibrium has led to a whole research programme on ‘business cycles’ based on dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) models that purport to consider the impact of various ‘shocks’ on a model capitalist economy – shocks like changes in the attitudes of investors or consumers and policies of governments (‘representative agents’).

Unfortunately, DSGE models have signally failed to offer any clear explanation of what is happening in modern capitalist economies, let along provide a guide to predicting future downturns in the ‘business cycle’ – see my post, https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2013/04/03/keynesian-economics-in-the-dsge-trap/.

Recently, two top-line economists, Roger Farmer (Keynesian) and John Cochrane (neoclassical) have tried to feel their way to a compromise position between whether capitalist economies can stay locked in below-trend growth after a slump or not.

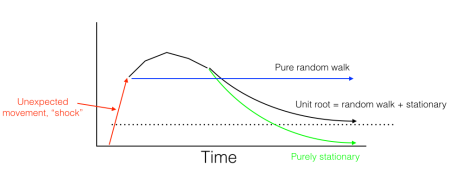

And it’s all about what is called unit roots. Unit roots are a statistical phenomenon where, say, when there is a collapse in output or unemployment, this may be only temporary and output or unemployment will start to return towards its previous trend, but not all the way. This contrasts with ‘stationary’ phenomena where the shock is eventually corrected and the previous trend is re-established and a ‘random walk’ where the trend remains at a new (lower) level permanently. The graph is from John Cochrane’s blog post (http://johnhcochrane.blogspot.co.uk/2015/04/unit-roots-in-english-and-pictures.html).

Roger Farmer has been arguing that economies can suffer a slump in demand and thus in output, investment and employment that can move an economy from one equilibrium trend to another lower one which is where it settles – and this change is due to a chronic weakness in demand not to changes in long-term supply-side factors like productivity or population growth, as neoclassical growth theory reckons (http://rogerfarmerblog.blogspot.co.uk/2015/04/there-is-no-evidence-that-economy-is.html).

Farmer reckons that there are both transitory and permanent elements in the business cycle, so output or unemployment can exhibit movements close to unit roots. Actually, a unit root description of a business cycle that does not return to the previous trend is very close to my own schematic characterisation of a depression as taking the form of a square root – see my post, https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2015/04/18/the-global-crawl-and-taking-up-the-challenge-of-prediction/.

Farmer reckons that business cycles are caused by changes in ‘animal spirits’: “My answer is that aggregate demand, driven by animal spirits, is pulling the economy from one inefficient equilibrium to another.” So “If permanent movements in the unemployment rate are caused by shifts in aggregate demand, as I believe, we can and should be reacting against these shifts by steering the economy back to the socially optimal unemployment rate.”

So Farmer reckons, as the business cycle is a unit root, it does not self-correct and governments must intervene to smooth out the fluctuations and get unemployment down. John Cochrane is not convinced of the need for government intervention, of course, but he does recognise that there can be a chronic or permanent element in changes in unemployment and it may not be totally self-correcting. A unit root is a good compromise, it seems.

Good news, eh! Keynesian and neoclassical economics have moved to a compromise in theory that capitalist economies do fluctuate (due to ‘shocks’ in demand or supply) and may not always return to previous trends. And something exogenous (government) may have to act to correct it.

The fact that neither neoclassical non-intervention policies nor Keynesian policies of macro-management had any effect in stopping the reappearance of the ‘business cycle’ from the 1970s onwards or controlling them appears to have escaped both Farmer and Cochrane. Instead, they continue to debate the nature of the ‘shocks’ to the system.

There is little doubt that capitalist economies are not ‘self-correcting’ and a level of unemployment or real GDP growth that existed before a major slump may well not return after the recession ends – indeed the current slow crawl of ‘recovery’ since the trough of the Great Recession in 2009 proves that with a vengeance.

And there is new evidence of that theoretically. A new working paper by Daron Acemoglu, Ufuk Akcigit, and William Kerr looks at the pattern of how economic disturbances propagate throughout the industrial and regional network (http://conference.nber.org/confer/2015/Macro15/daron.pdf). They examine several types of disturbances such as changes in Chinese imports, government spending and productivity. Some of these ‘shocks’ propagate upstream through the value chain, from retailers to suppliers. They call these demand shocks. Others move in the opposite direction, and they call these supply shocks.

Keynesian blogger, Noah Smith is very excited at this research. As he puts it: “the implication is that the rosy picture of the economy as a smoothly functioning machine isn’t necessarily an accurate one. The tinker-toy web of suppliers and customers and regional economies in Acemoglu et al.’s paper is a fragile thing, easily disturbed by the winds of randomness”. http://www.bloombergview.com/articles/2015-05-01/a-little-disruption-can-cause-a-big-economic-shock.

The authors of the paper conclude: “Quantitatively, the network-based propagation is larger than the direct e§ects of the shocks, sometimes by several-fold. We also show quantitatively large effects from the geographic network, capturing the fact that the local propagation of a shock to an industry will fall more heavily on other industries that tend to collocate with it across local markets. Our results suggest that the transmission of various different types of shocks through economic networks and industry interlinkages could have Örst-order implications for the macroeconomy.”

Also, Smith concludes that “one of the biggest and longest-lasting economic debates is whether government spending can affect the real economy. Lucas and others (the neoclassicals) have claimed that it can’t. But in Acemoglu et al.’s model, it absolutely can, since the government is part — a very big, very important part — of the network of buyers and sellers.”

But all the paper confirms, by using bottom-up input-output connections, is that the collapse or bankruptcy of a large firm or bank or sharp change in trade can trigger a crisis by cascading through an economy. This shows how slumps can start but suggests that they are due to random events. That does not explain the recurrent nature of slumps and so explains nothing.

Smith claims that the paper “would solve the problem of what causes recessions. Currently, we have very little idea of what tips economies from boom over to bust — there is usually no big obvious change in productivity, technology or government policy at the beginning of a recession. If the economy is a fragile complex system, it might only take a small shock to send the whole thing into convulsions.”

So the cause of recessions is random shocks that multiply. That is no more an explanation than that proffered by Nassim Taleb in his book, Black Swan, or by the heads of the American banks during the financial crisis, that it was a chance in a billion (https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2010/05/26/how-the-official-strategists-were-in-denial/).

In none of these current debates is there any mention of the role of profit in the ‘business cycle’ in what is essentially a profit-making system of production. Business cycles are back according to macroeconomics – rather belatedly. But it’s random or it’s not random; it’s demand or it’s not demand; it’s monetary or it’s not monetary. Mainstream theory remains in a fog of confusion.

REMEMBER: SEE MY LATEST THOUGHTS ON ECONOMIC EVENTS AT MY FACEBOOK SITE:

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Michael-Roberts-blog/925340197491022

No comments:

Post a Comment