Readers of this blog will know that from its very beginning over five years ago, I have argued, ad nauseam, that after the end of the Great Recession in mid-2009, the world capitalist economy entered what I have called a long depression, see

https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2013/02/10/why-is-there-a-long-depression/.

What I meant by this was that the trajectory of the world real GDP growth and investment took what I described as a square-root shape. A relatively high trend growth rate was interrupted by a sharp drop, then a sharpish recovery before growth resumed but this time at a much lower level than before.

Schematically, it would look like this – and in reality.

This view, that capitalism is in a Long Depression, will be the main message of my upcoming book to be published (I hope) this summer.

However, there are many voices who do not agree that world capitalism is in a downward phase or wave or in a depression. Some, indeed, reckon that capitalism is in an upward wave of growth and investment and there has been no ‘stagnation’ or depression. I won’t deal with these arguments in this post. Instead, I shall add to the data supporting my view that the trajectory of depression is still in place.

As I write, the world’s leading central bankers and economists are in Washington for semi-annual meeting of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank. And in its latest World Economic Outlook report (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2015/01/index.htm), IMF economists explain that the global economy continues to crawl along at well below the post-war average trend growth rate, with little sign of improvement.

The IMF argues that the ‘potential output’ of the world economy is growing more slowly than before. In the advanced countries, the decline began in the early 2000s; in emerging economies, after 2009. The concern is that the world economy is now characterised by chronic weak investment, low real and nominal interest rates, credit bubbles and unmanageable debt. Christine Lagarde, head of the IMF, described the world’s current economic performance as “just not good enough”.

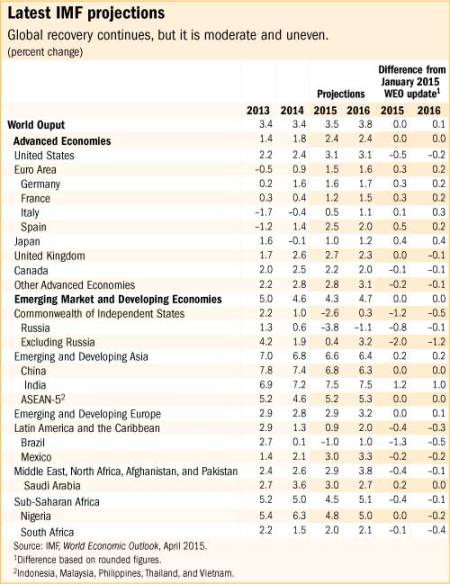

The IMF expects real GDP growth in the advanced capitalist economies to pick up from 1.8% in 2014 to 2.4% this year. It needs to see that acceleration to achieve its forecast of world growth at 3.5% this year because growth in emerging markets, particularly in China and Russia, is slowing or even falling, so that growth there will be only 4.3% in 2015 down from 5% in 2013.

There are other forecasts and indexes less followed than that of the IMF that also show that the world economy is still crawling along. The global economy is mired in a “stop and go” recovery “at risk of stalling again”, according to the latest Brookings Institution-Financial Times tracking index. This ‘Tiger index’ shows measures of real activity, financial markets and investor confidence compared with their historical averages in the global economy and within each country. The Tiger index graph for global growth looks like the ‘square-root’ trajectory that I forecast back in 2009 for the world economy during and after the Great Recession.

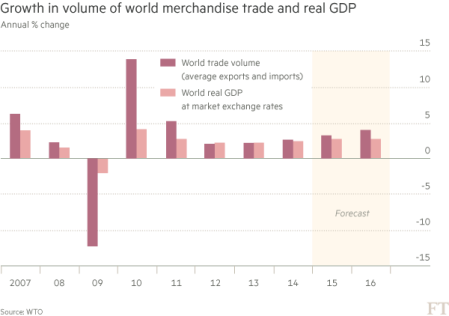

Even more telling is the annual report of the World Trade Organisation just out. Global trade is poised for at least two more years of disappointing growth, according to the WTO. The WTO reckons world trade will grow just 3.3% this year, below the rate of world GDP growth expected by the IMF. It’s bad news whenever trade grows more slowly than GDP because it means the economies cannot get out a depression (Greece) or slow growth by exporting as external demand is even weaker than domestic demand.

You see, for at least three decades before the 2008 financial crisis, in the era of ‘globalisation’, world trade regularly grew at twice the rate of the world GDP. With last year’s growth of 2.8%, global trade has now expanded at, or below, the rate of the broader global economy for three straight years.

Roberto Azevedo, WTO director-general, blamed disappointing trade growth in recent years on the sluggish recovery from the financial crisis. He also warned that economic growth around the world remained “fragile” and vulnerable to geopolitical tensions.

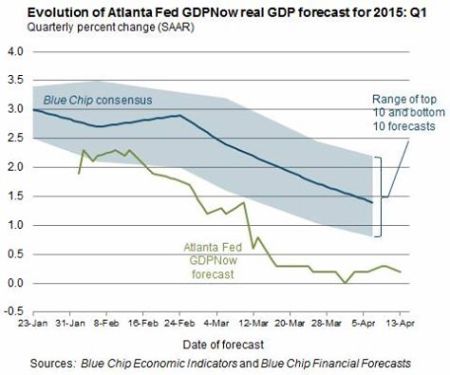

And then there is the high frequency measure of the US economy provided by the Atlanta Federal Reserve Bank. Its latest estimate is that the US economy has slowed to just a 0.2% annual rate as of 14 April. The apparent significant slowdown in the first quarter (blamed by the mainstream on a ‘bad winter’) is now carrying into the second quarter of 2015.

So 2015 has not made a good start in meeting the forecasts of the IMF for faster US growth of over 3% this year – by the way, the IMF has made such a forecast and got it wrong for the last four years.

Now Chris Dillon runs an excellent and interesting blog called, Stumbling and mumbling. In a recent post, he argued that economists could not be expected to forecast anything, only to try and explain what is happening in the here and now, http://stumblingandmumbling.typepad.com/stumbling_and_mumbling/2015/04/forecasting-vs-explaining.html.

He went on to point out, as I have just done above, that the IMF and the other leading official institutes had miserably failed to forecast the Great Recession or the subsequent slow recovery, being perennially optimistic about how things would pan out.

But Dillon reckoned that heterodox economists were little better in their forecasting, although he was wrong to say that Steve Keen did not forecast a credit crunch for the US economy in 2007-8 (see my paper, The causes of the Great Recession).

Like so many others, Dillon reckons the Great Recession was just a financial crisis caused by the collapse of the banks, which is really a description of the crash not an explanation. But he then put out a challenge: “Many of macro’s critics are begging the question: they are assuming that the economy could be predictable, if only we had a good enough theory. I doubt this. Now, this is just a hypothesis – albeit one consistent with lots of evidence. If you want to show I’m wrong, point me to some forecaster who foresaw both the recession of 2008-09 and the growth either side thereof. Or, failing that, show me forecasts for future years which successfully predict both growth and recessions.”

Well, as the quantum physicist, Niels Bohr once said, “Prediction can be very difficult, especially if it is about the future”. But I might be able to take up that challenge by Dillon. This is what I said back in 2005 in my book, The Great Recession, eventually published in 2009. “There has not been such a coincidence of cycles since 1991. And this time (unlike 1991), it will be accompanied by the downwave in profitability within the downwave in Kondratiev prices cycle. It is all at the bottom of the hill in 2009-2010! That suggests we can expect a very severe economic slump of a degree not seen since 1980-2 or more”.

As for the second part of Dillon’s challenge (how would the world economy grow after the end of the Great Recession?), then readers can consider what I predicted five years ago and mentioned at the start of this post (and for that matter also in my book, The Great Recession, back in 2009). So far, that prediction – for a long depression – has broadly worked out. In addition. I have argued in many posts that this depression will end but probably not before another severe economic slump, which is likely to begin within the next 12-18 months and last for a similar period through to 2018 or so. That’s a prediction.

And I think part of any scientific analysis is to make such forecasts or predictions to test a theory and its real outcomes. It is not good enough to just explain in hindsight (see my posts,

https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2014/06/30/rethinking-economics/ and

https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2012/11/22/bayes-law-nate-silver-and-voodoo-economics/).

For that matter, Marx himself made predictions arising from his theoretical analysis. He did not have sufficient data to make accurate predictions about oncoming slumps and recoveries, although he continually tried to find such data to do so. But his law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall does make a fundamental prediction: that the capitalist mode of production will not be eternal, that it is transitory in the history of human social organisation, because it has a use-by date. The law of the tendency predicts that over time there will be an actual fall in the rate of profit globally, delivering more crises of a devastating character. And what work has been done by modern Marxist analysis confirms that the world rate of profit has fallen over the last 150 years (see Maito, Esteban – The historical transience of capital. The downward tren in the rate of profit since XIX century and Long-Term Movement of the Profit Rate in the Capitalist World-Economy).

Obviously, sucking a forecast out of the air is no better than choosing a number in a lottery. A forecast is only as good as the theory behind it. I reckon Marx’s theory of crisis provides the best explanation of the Great Recession in 2008-9 and also allows us to discern the stage through which capitalism is going and where it is going. So I based my forecasts back in 2005, in 2009, and now, on that theory and the law of profitability (as developed by others and me). But, as Engels often said: the proof of the goodness of a pudding is in the eating.

No comments:

Post a Comment