News that Greek prime minister Tsipras had moved his finance minister Yanis Varoufakis from direct negotiations with the Eurogroup suggests that the Syriza government is preparing to make more concessions to the Troika to reach agreement on the terms of the release of outstanding funds from the EU and the ECB under the four-extension of the second bailout package. Varoufakis has been replaced by Euclid Tsakalatos, the Oxford-educated economist and previously shadow finance minister when Syriza were in opposition (see my post, https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2015/01/21/syriza-the-economists-and-the-impossible-triangle/). Tsakalatos is possibly more ‘moderate’ and certainly more acceptable for the Eurogroup finance ministers to deal with than the ‘charismatic’ Varoufakis, whom they all seem to hate.

Tsipras’ move towards making more concessions and perhaps dropping the non-negotiable ‘red lines’ that Syriza won’t allow to be breached would probably get support from the Greek people, at least if the current opinion polls are correct. One poll found that 79% of Greeks want to stay in euro and 50% want to reach a compromise rather than a rupture (36%). Around 63% of Greeks want to avoid a default on the Greek government’s debts. And if there is a deal that breaks the red lines, then Greeks would prefer a national unity government (44%) rather than a referendum (32%) or new elections (19%) to confirm it. Syriza still leads in the polls with 36% of the potential vote compared to 22% for the right-wing New Democracy; 5% for the social democrat Potami, 3% for the bankrupt PASOK and now just 5% for the fascist Golden Dawn and the Communists.

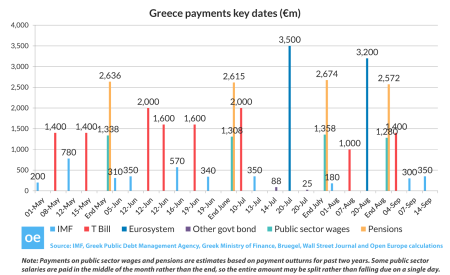

Time is running out to reach any sort of deal that might pass muster with the Greek people and avoid default on debts and possible exit from the Eurozone. The government has managed to scrape together enough cash by appropriating reserves from local authorities and other government agencies so that it can pay upcoming debt obligations to the IMF during May. But it is unlikely to have enough to repay the IMF in June and certainly not enough to meet €3.5bn bill to the ECB in July – unless it does not pay its workers their wages and pay out state pensions.

Ironically, the Syriza government is still running a budget surplus of €1.7bn in the first quarter of this year. It has managed this by just not paying its bills to government suppliers or to the health service and schools. In doing this, it can meet the wages of public sector workers and pensions. The problem is that unpaid taxes are rising steadily, reaching €3.5bn in Q1, although the growth in this deficit has been slowing. People, especially rich people and businesses, are unwilling to pay their tax bills if they think that Greece will soon be thrown out of the Eurozone and the government will default on its debts and devalue Greek euros. They want to hold onto all the euros they have got.

So far, the ECB has been bankrolling the Greek banks as deposits there keep falling. But Greek banks are beginning to run out of suitable ‘collateral’ for ECB funding, namely Euro bonds from the Euro institution, EFSF, that the banks hold from the recapitalisation carried out in 2013. And the ECB will stop credit altogether if the Greek government defaults on its debts.

When the negotiations began on a four-month extension to the existing ‘bailout’ package last February, I reckoned that a deal was likely but that negotiations would be long and tortuous, and so it has turned out. Even if there is a deal to release the €7.2bn still available under the old bailout package, a new package to fund the Greek banks and meet further IMF debt repayments through to April 2016 will be slow to reach.

There is a possibility that if Syriza makes enough concessions on: reducing pensions; raising VAT; allowing privatisations and introducing ‘reforms’ in labour markets, then it could get the €7.2bn and also negotiate a third package for after end-June that would meet future ECB and IMF repayments and yet not impose too heavy an austerity package. Apparently, Tsipras, Merkel and the Eurogroup have agreed that the primary budget surplus target will be reduced from 3-4% of GDP a year to around 1.5%. And if the Eurozone economy starts to recover, that could also pull up the Greek economy through higher exports and more inward investment. That is the scenario that Tsipras and the Syriza leaders are looking to.

Indeed, Varoufakis spelt out how such a scenario might just work if the Euro leaders were just a little more amenable (see http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/greece-debt-deal-by-yanis-varoufakis-2015-04#cMxRQSLwJzBQxIw2.99). Varoufakis has previously said that the aim should be to convince the Euro leaders and the financial markets that giving the Greeks some ‘breathing space’ would allow the economy to recover and this will help European capitalism. And the aim right now is “to save capitalism from itself”, and not launch ridiculous socialist measures as “we are just not ready to plug the chasm that a collapsing European capitalism will open up with a functioning socialist system” (see my post, https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2015/02/10/yanis-varoufakis-more-erratic-than-marxist/).

Of course, this ‘way out’ means that Syriza will still be conducting (if ‘lighter’) fiscal austerity by running a surplus on the government budget at a time when Greek unemployment remains at over 25% and the economy is still contracting in real and nominal terms. Indeed, Greeks have already suffered a fiscal austerity adjustment equivalent to 20% of potential GDP since 2009.

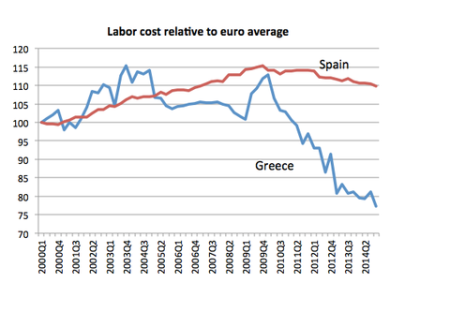

And Greek workers have taken a huge hit in order to restore Greek corporate profitability: a 25% cut nominal private-sector labour costs, or more than 30% relative to the euro average.

But all these cuts have failed to reduce the government debt ratio one iota. On the contrary, the government debt ratio is now at 175% of GDP, way higher than in 2010. Under any deal with the Troika, this debt burden would not be reduced as there would be no cancellation of the debt with the EU ‘institutions’. The Greeks can never pay back this debt and it is ludicrous to expect them to do so. And as we know, around 90% of these Troika loans did not ‘bail out’ Greeks but were used to repay French and German banks and American hedge funds who held Greek bonds and were demanding their money back. The monies owed to these finance capitalists was merely transferred to the official sector (the EU ‘institutions’ and the IMF) – see my post, https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2015/02/21/greece-third-world-aid-and-debt/.

It’s true that the EU loans do not start to be paid back until 2020, but the Eurogroup is insisting that the Greeks begin the process of debt reduction in advance through higher taxes and controls on spending, even though Greek households are still in a mire of poverty and public services in health, education and housing are in chaos. For the Euro leaders, it is better to preserve the illusion that member states must pay their debts, in order to ‘encourage’ the others and maintain the EU’s fiscal pact. Also, they aim to restore Greek capitalism by raising profitability, not to restore Greek household incomes.

Back in February, I posed the issue as an impossible triangle. Syriza could not reverse austerity, stay in the euro and remain united as one party in government. One or more of these aims would have to go. It seems that the Tsipras will opt for staying in the euro, even if he cannot reverse austerity or write off Greek government debt. The question then becomes a political one: what will the left within Syriza do? Will they too swallow any deal, especially if Tsipras puts it to a referendum of the people and wins the vote? Or will they split the party and force Tsipras into an alliance with the opposition (national unity) to get any deal approved by parliament?

There is still the possibility that the austerity terms demanded by the Troika are just too much for the Syriza leadership to accept and the Greeks will opt to default on the repayments in June. The IMF allows a 30-day ‘grace period’ to meet overdue debts, so default is not technically immediate, although there would probably be a run on the Greek banks. The government would have to impose capital controls to stop money leaving the country or even just under the mattresses. Introducing capital controls is not breaking any Eurozone rules, so technically, Greece would still be a member of the Eurozone. But the run on the banks would mean that the ECB would either have to step in fund the gap or the banks would go bust. The question of Greek membership of the Eurozone would then be posed.

The government could continue to claim that the euro was the Greek currency and not introduce any new drachma. But euros would soon become scarce to pay government workers and for businesses to pay for imports and their workers wages. The Greek economy would head into an even deeper slump down the road. So devaluation and a new Greek currency would not be long in coming, to try to avoid a meltdown. But devaluation would mean that Greek businesses would find it even more difficult to pay their euro bills and many would go bust. Inflation would rocket and the new drachma would plunge in value. It would be another form of meltdown. These are the outcomes for the Greek people, deal or no deal, under capitalism.

The alternative to grasp the nettle: demand the cancellation of the euro and IMF loans (the original demand of Syriza) or default; impose capital controls, take over the Greek banks and appeal to the Greek people for support and the European labour movement. Let the Euro leaders make the move on Eurozone membership, not Syriza. The problem is that now the Greek people have been led to believe that there is only one way out: a deal with the Eurogroup on increasingly bad terms. The alternative of a socialist plan for investment and a Europe-wide appeal is not before them. (see my post,

https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2015/03/03/greece-breaking-illusions/).

The Tsipras-Varoufakis approach of concessions now and hope for a better capitalist economy down the road could work for a short while. But it won’t reverse the terrible losses in incomes, jobs, education and health that those Greeks who have not been able or willing to leave the country have suffered. And what happens when the next slump in the world economy comes along?

No comments:

Post a Comment