Most governments in capitalist economies have engaged in what is loosely called ‘austerity’ policies since the end of the Great Recession in 2009. More precisely, austerity policies are those where the government aims to reduce its annual deficit on spending and revenues and shrink the overall debt burden, plus introduce ‘reforms’ to weaken the labour rights and conditions at work to keep wage costs down for the capitalist sector. The fiscal part of these austerity measures mainly involved cutting back on government spending, both in public sector employment, wages, public services and investment projects.

Those economists and governments that advocated austerity claimed that by getting debt ‘under control’, costs would be reduced and companies would invest, consumers would spend and economies would recover quickly. Keynesians and others who opposed these measures reckoned that austerity would drive down ‘aggregate demand’ as government spending was cut, taxes raised and wages held down. The way out of the crisis was to borrow more, not less and spend more not less.

The debate continues. In my view, both sides are right and wrong. See my posts on this:

https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2012/04/14/the-austerity-debate/ and

https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2012/09/30/can-austerity-work/

The Austerians recognise that the key to a capitalist economy recovering is to reduce costs for the capitalist sector by cutting wages and government taxation so that profitability can rise. Raising wages or increasing government sending, as the Keynesians advocate, would reduce profitability at a time when it needs to rise. However, the Keynesians recognise that, once an economy is in a slump and labour incomes are falling, cutting them further can worsen the fall in consumer spending and investment demand and for some time. It’s not quite Catch 22; but looks like it for a while.

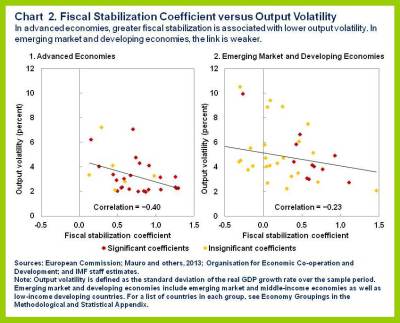

In a recent study, the IMF considered the question of whether austerity worked. The IMF found that if governments did not spend too much when economies were growing and spent more when economies were in a slump, then this would act as a counter-cyclical buffer to the volatility of the capitalist sector. The IMF quantified this effect as cutting “output volatility by about 15 percent, with a growth dividend of about 0.3 percentage point annually”. The IMF optimistically reckoned that “Stability, growth and debt sustainability could all greatly benefit if measures that destabilize output, such as spending increases in good times, were avoided”.

But this is the classic sort of fiscal management policy advocated by mainstream economics back in the 1960s that supposedly was the answer to controlling capitalist booms and slumps. Governments could smooth economic fluctuations by judicious (and even automatic) fiscal ‘stabilisers’. Yet this policy (in so far as it was even implemented) proved a total failure during the 1970s, when the major capitalist economies experienced inflation and unemployment together and government fiscal management failed. Indeed, governments probably increased volatility by stimulating or applying austerity at the wrong times.

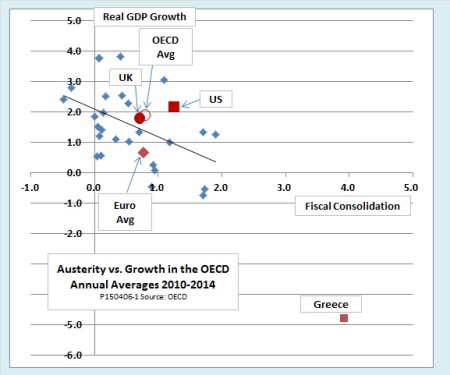

Anyway, has austerity worked in getting economies to recover quicker since 2009 or have austerity measures made it worse? See the graph below covering 30 advanced capitalist economies for changes in real GDP growth and reductions in government budgets since 2010 (from http://www.economonitor.com/dolanecon/2015/04/08/did-austerity-work-in-britain-one-chart-tells-it-all/) . The further to the right a country, the more austerity there has been – with Greece leading the way. The further up the graph a country is, the more growth there has been since 2010.

The graph trendline appears to show that tightening the budget by one percent of GDP cuts about half a percentage point off the growth rate, even if we omit Greece. But the correlation is not very strong. The US underwent more fiscal consolidation than the UK in 2010-2014, but it also had better growth. On the other hand, the countries of the Eurozone, on average, grew more slowly than the OECD average despite a similar average level of austerity. So other factors than the fiscal policies of governments were much more important for post Great Recession growth (see my post,

https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2012/10/25/uk-and-us-gdp-and-anglo-saxon-angst/.

As for the other arm of austerity, ‘labour market reform’ (i.e. weakening trade unions, increasing the ability of employers to hire and fire at will, deregulating contracts and hours and job qualifications), have they worked? These measures are advocated by the IMF, the OECD and by the European institutions in their current negotiations with Greece. Well, a new study by IMF economists found no evidence that “deregulatory labour market reforms could have a positive impact in increasing economies’ growth potential”. What they found was that more competition among capitalists in markets and higher investment spending contributed much more to boosting productivity than squeezing the conditions for the workforce.

What the IMF did not consider was that while more investment in new technology might raise productivity per worker more, cutting wage costs and weakening labour’s bargaining power can deliver more profitability quicker. It might be short-sighted, but the capitalist mode of production does not take the long view.

In short, austerity has not worked in restoring trend economic growth, although it has not made things much worse either. The problem is that cutting wage costs and holding back on government investment and spending has not sufficiently restored profitability and reduced debt to allow a significant rise in new investment. But the alternative policy of Keynesian-type government spending might have helped labour a little, but it would not have boosted investment and growth either, as it would have lowered profitability. Governments appear helpless to change things either way. Another recession may do the trick

No comments:

Post a Comment