Crude oil prices have dropped to five-year lows in just a few months. And the reason is clear: it’s supply and demand! On the supply-side, the most significant development has been the accelerating expansion of shale oil and gas production in North America, mainly in the US.

Oil and gas reserves are trapped in layers of shale rock and can be released by a process of hydraulic water pressure called fracking. By sinking hundreds of rigs in quick succession, shale rock can produce significant supplies of tight oil and natural gas – and this process in North Dakota, Texas and other areas has turned US oil production round. US oil output up to now had been based in traditional deep oil reserves in Texas, Louisiana and the Gulf of Mexico. US production was in decline from the mid-1970s to around 4mbd and falling. But with shale, annual output has rocketed back to 9mbd, near previous peaks. Fracking for tight oil and gas is now spreading across the globe as those countries with large shale reserves look to exploit it in Poland, China, Europe and even the UK.

The other side of the price equation is demand. Global demand for energy, particularly oil, has slowed. That’s mainly because global economic growth has slowed since the Great Recession ended. China has led the way with slowing growth, along with the other large emerging economies, like Brazil and India; and the major advanced capitalist economies remain in ‘low gear’ (see my post, http://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2014/11/08/the-world-economy-in-low-gear/). Industries are increasing their use of fossil fuels at a slower pace than expected, while transport demand is in decline (Americans are driving less). Energy conservation has been stepped up and energy intensity (energy per unit of output) is falling everywhere. All the international energy agencies now expect oil and gas prices to stay at these new lows for some years ahead.

The biggest losers are those countries that rely on energy exports to make their money: Saudi Arabia, the rest of the Arab oil states, super-rich Norway, super-poor Venezuela, Mexico and, above all, Russia. The Saudis have launched a counter-offensive. With more than five times the reserves of American shale, they are taking on the shale producers by increasing production in order to drive down the price to the point where shale producers start losing money (their production costs are way higher than the Saudis: about $50/b to $25/b). So far this has not worked and shale production continues to rise. But the Saudi policy is destroying the revenues of other OPEC producers like Venezuela – and Russia.

Putin may have faced up to ‘the West’ over Ukraine and refused to budge but, as I argued in a previous post (http://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2014/11/10/from-poroshenko-to-putin-its-all-downhill/), the West has been winning the economic battle and the oil price has been the major weapon. The collapse in the oil price has exposed the weakness of the Russian economy.

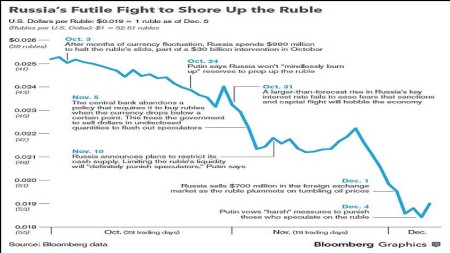

Just a year ago, Russia’s stockpile of dollars from energy exports stood at more than $515bn. Now as oil revenues have dissipated and sanctions on Russia imposed by the West over Ukraine have been applied, Russia’s trade surplus has diminished and the flight of capital by oligarchs and others out of Russia and the rouble has rocketed to $120bn a year. As a result, FX reserves have dropped below $400bn and the rouble has plunged in value to the dollar by 40% this year, invoking a sharp rise in the inflation of prices in Russian shops and shortages of imported goods.

$400bn is still a large reserve and the Russian central bank has tried to prop up the rouble by selling its dollars and buying the Russian currency in FX markets. But it did not work. Then the central bank just let the ruble go to save dollars. And the rouble plunged further. Now it has started buying roubles again with its reserves to stop the fall, again to no avail.

Central bank policy is all over the place. And this is worrying Putin who has begun to criticise his own bank appointees. The problem is that much of these reserves cannot be used to prop up the currency because enough must be kept to cover payments for essential imports (the IMF recommends at least three months worth of imports). If reserves drop below that level, the rouble will go into even more meltdown as foreign lenders (mainly European banks) pull out their money. Also the fall in the ruble means that all those Russian companies with big dollar debts and loans, particularly Russian banks, face huge dollar bills that they cannot meet.

According to the Russian Central Bank, the country has to repay $30bn of debt this month and another $138 bn in the next 18 months. Only 2% of this debt is owed by the government, while non-financial enterprises accounted for more than 60%, the rest mostly belong to the banking debt, including Russia’s largest bank – the state-owned bank Sberbank.

So they are asking for (and getting money) from the government to bail them out. State oil giant Rosneft, for example, has asked for $44bn, equalling more than half the remaining balance in the so-called Wellbeing Fund that’s earmarked to support the pension system. VTB Bank and Gazprombank have already gotten more than $7 bn from the Wellbeing Fund and are asking for billions more. If FX reserves and wealth funds are used up to bail out the banks, then planned infrastructure projects will be dropped and pensions will come under threat. And the three-month import limit will get closer. At current rates of decline in FX reserves, that limit could be reached by summer 2015.

Putin‘s annual address to the Russian parliament last week showed he was getting worried. He even offered a complete amnesty to oligarchs who have been spiriting their money out of Russia like a waterfall in the last few months. “I propose a full amnesty for capital returning to Russia,” Putin said. “I stress, full amnesty.” “It means,” he continued, “that if a person legalizes his holdings and property in Russia, he will receive firm legal guarantees that he will not be summoned to various agencies, including law enforcement agencies, that they will not ‘put the squeeze’ on him, that he will not be asked about the sources of his capital and methods of its acquisition, that he will not be prosecuted or face administrative liability, and that he will not be questioned by the tax service or law enforcement agencies.”

In Russia, two of the major classes of people who have large amounts of capital overseas are organized criminal groups and the so-called oligarchs. In stressing that there would be no prosecution, Putin appeared to explicitly leave the door open to money obtained illegally. “He’s talking to people who have engaged in corporate raiding,” said Professor Louise Shelley, founder and director of the Terrorism, Transnational Crime and Corruption Center at George Mason University in Fairfax, VA. “There are thousands of cases where people who have used criminal processes and false documents to acquire assets. He’s talking to organized crime figures who have taken over businesses.” She added, “There are no large fortunes that are entirely clean money in Russia.”

Assuming the oil price stabilises at around $60/b next year, Putin can avoid a debt crisis next summer, if he can squeeze Russian corporations to buy roubles with their dollar export revenues (a form of capital controls) and to bail out the banks with government reserves. Putin is doing just that. But that does not save the domestic economy. The sanctions plus the collapse in oil prices have pushed the Russian economy into recession. The government admitted that the economy would contract by about 1% next year, with investment falling 3.5% and average household incomes down nearly 3% in a year! Indeed, for the first time in 15 years, living standards for the average Russian will fall in 2015. A freeze on inflation-linked pay has been imposed and inflation is rising at nearly 10% a year now.

Putin may be very popular because of his foreign policy over Ukraine and ‘standing up’ to the West, but his popularity will now suffer because of his domestic policy. Russian-style austerity is coming. Whereas government spending has risen an average 10% a year in the past decade, it will now be cut. Cutting military and police spending is politically impossible because Putin needs the support of the security establishment so he can rely on them in case of social unrest. This means the government will have to target investments, benefits and salaries. Last week, Putin announced a 5% cut in real terms from 2015-2017 by reducing “ineffective spending,” except for defence and security. Putin used to promise Russians that their country would overtake Germany as the world’s fifth-largest economy by 2020. In May 2012, he signed a decree pledging to increase real wages by half by 2018. Those promises are now dead in the water.

Putin continues to rely on his Ukraine policy for popularity and Ukraine’s economy is in an even worse state. Ukraine’s central bank reserves have dipped below the $10bn mark for the first time since 2005 after making a gas payment to Russia’s Gazprom (see my posts on Ukraine). The IMF will probably hand over another $2.7bn in funding to tide the Kiev government over. But it is clear that Ukraine needs another $20bn over the next two years to handle the war in the east and fund debt repayments. An IMF mission arrives tomorrow to plan a massive austerity plan for the Ukrainian people in return for funding.

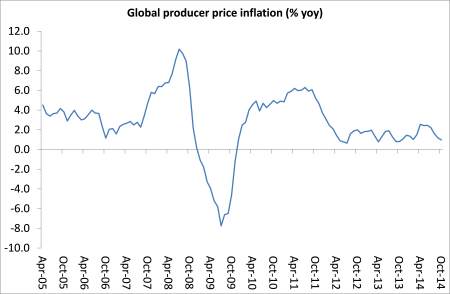

But probably the most important aspect of the collapse in the oil price is the spectre of global deflation. World inflation has been very low since the Great Recession, another indicator of the Long Depression that the world economy has been locked into. But what inflation of prices there has been has mainly been due to the sharp rise in energy prices. Non-energy price rises have been minimal. Now, with the sharp fall in energy and other commodity prices (metals, food etc), deflation is the spectre haunting the globe.

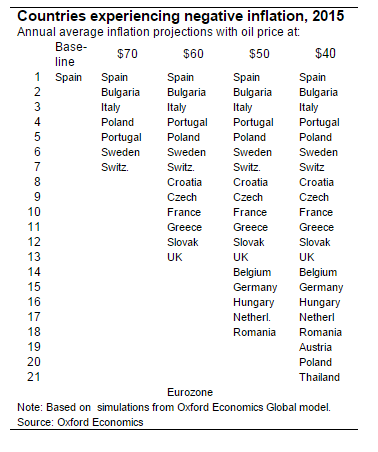

Oxford Economics finds that if oil prices were to fall to as low as $40/b, then 41 out of 45 countries it follows would experience deflation.

Some argue that this is good news. This is the line of some neoclassical economists and the Austrian school. Falling prices, particularly in energy and food, will raise consumer purchasing power, and help boost demand and thus economic growth.

But for profitability, it is bad news. Inflation of corporate producer prices is another temporary counteracting tendency to falling profitability. If it disappears, then the downward pressure on profitability from any new technology investment will be greater as falling prices squeeze profit margins. In that sense, deflation is not good news for the capitalist sector, especially if it is burdened with heavy debts (small businesses in particular). So the crisis brewing for Russian businesses may be followed by others. It could be another factor leading to a new global slump, this time based in the non-financial productive sector of capitalism.

No comments:

Post a Comment