The temporary truce between Ukraine and Russia seems over, with the news that the Kiev government has launched a new offensive against the separatist enclaves in eastern Ukraine, which are backed by the Russians.

This military upsurge has followed quickly after the two elections in Ukraine. The first was in the bulk of the country, where the pro-EU parties won a significant majority in a new parliament in Kiev, dividing the bulk of the vote between the party of President Poroshenko, the chocolate manufacturing oligarch and the neo-liberal party of the current prime minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk. The second was in the separatist areas, where the pro-Russian militia groups rule by the gun. This provoked the new action by the Ukraine military and the corresponding mobilisation again across the border by Russian forces.

Ironically, just before this Ukraine and Russia had finally agreed a deal for Ukraine to get its energy supplies for the winter, with Ukraine agreeing to pay its back debts of $1bn and to pay for future energy in instalments. The issue here, however, is whether Ukraine is really going to find the money to pay for it. It is going to need a substantial commitment from the EU and the IMF, both of which are stalling on stumping up more money because the Ukraine economy is on its knees and both the government and Ukraine’s private sector are close to defaulting on their debts.

Ukraine’s central bank reserves have fallen to a near decade low of just $12.6bn, after the country spent billions servicing foreign debts, protecting the currency and repaying parts of a Russian gas bill.

The decline in reserves from $16.3bn at the end of September pushes Ukraine perilously close to a danger zone where its reserves only cover a few months of imports and Ukraine is unlikely to receive the second tranche of its $17bn loan programme from the IMF. Kiev had expected that a second tranche, worth $2.7bn, would come in December after the Fund’s mission later this month. But that now looks unlikely because, despite the election of a new parliament, a new coalition government has not yet been formed.

And $17bn anyway is not likely to be enough. That’s because the Ukraine economy has imploded, as predicted last August (see my post, http://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2014/08/31/ukraine-a-grim-winter-ahead/). The economy has contracted by nearly 10% in one year, as a result of the collapse of production in mining and other basic industries, much of which are in the separatist areas, and, of course, the ‘collateral’ damage from the war has been significant. So it is more likely the IMF will have to cough up nearer $20bn, and with the real risk that it may never see that money paid back.

So Kiev only has €760m in aid from the EU this year. The finance ministry says it has enough funds to cover its external debt obligations until the end of January, but Kiev has asked Europe for an additional $2bn euros to cover its gas company Naftogaz’s bills for the current heating season. And the Russians are expecting $4.5bn in payments for energy supplied.

Ukraine’s currency, the hryvnia, continues to dive to new lows against the dollar and the euro, making payments for imports and existing debts ever more difficult. Ukraine’s public don’t want to hold hryvnias and desperately look for dollars and other foreign currencies. Earlier this year, the IMF estimated that if the hyrvnia dropped below 13 to the US$, then Ukraine’s debt burden would be too much to manage on its own. The currency is now below that level.

And the government is still supposed to honour its existing debts, repaying bonds that mature in 2015. Usually governments just issue new bonds to pay for old ones maturing. But who wants to buy Ukraine government bonds now? And who has the greatest burden of foreign currency debt among emerging capitalist economies? First, Romania (within the EU) and then Ukraine.

Ironically, the existing bonds are mostly owned by Russian banks. In addition, an American hedge fund Templeton owns about $5bn worth, or 40%, which they bought last year as a punt on Ukraine getting IMF support and turning things round. Both the Russians and the Americans are looking sick right now.

What’s worse is that the former ousted pro-Russian president Viktor Yanukovich had arranged a special €3bn bond from Putin to help out before he was booted out and there is a clause in that contract that allows Putin to ask for his money back if Ukraine government debt rises above 67%, or two-thirds of GDP. Well, given the fall in GDP this year and the collapse of the currency, that debt ratio has been reached now. The EU could bail Ukraine out but wants Ukraine to sign a free trade deal first. The Russians say if the trade deal is signed, they will call the bond in. So the EU has postponed a trade deal until the Russian special bond expires at the end of 2015.

Putin could engineer a default by calling in that bond. The problem is that it would mean the Russian banks taking a big hit to their balance sheets. Indeed, Russia itself is in serious economic trouble. With falling oil prices and sanctions imposed by the EU and the US on Putin, the Russian rouble has taken an almighty plunge too. Last week the rouble fell 8%, the biggest weekly fall in eleven years.

The Russian central bank has been trying to prop up the rouble by selling its FX reserves of dollars. Russia has built up a sizeable arsenal of dollars and gold over the years of high energy prices, but now it is leaking these like a boat with a big hole. So bad was the recent leakage that it decided to stop selling its reserves and let the rouble slide. And slide it did – to a record low against the dollar. And nobody wants Russian government bonds or to invest in Russian companies any more. On the contrary, Russia’s oligarchs want to get their money out. But as they rely on Putin’s support, they must be careful.

Russia’s FX reserves have fallen to $439bn from $509bn at the start of the year and Russia’s former finance minister and current chairman of the Committee of Civil Initiatives Alexei Kudrin reckons that available reserves now barely cover six months of imports at current prices. Six months is the critical level to insure the Russian population against the possibility of severe hardship in case the crisis deepens and the Russians are deprived of foreign goods. (Russia imports a large amount of staples including butter, cheese, and meat.)

Oil and gas revenues still account for almost half of Russia’s federal budget along with 10% of the country’s GDP and with prices dropping, Putin looks set to impose a big round of austerity on the Russian people. Russia’s Ministry of Finance is proposing a 10% cut in the budget over the next three years.

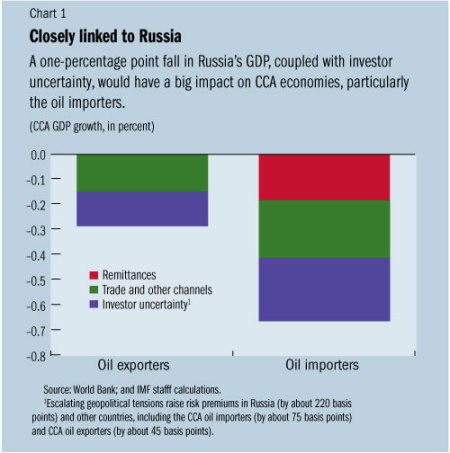

The Russian economy is virtually in recession now and Russia’s ‘empire’, the so-called Commonwealth of Independent States and the oil-rich Kazakhstan and not so rich Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Belarus, Armenia and Azerbaijan, are also taking the pain. The problem is the massive trade dependency these countries have on their former soviet master. Kazakhstan, the second largest of the ex-Soviet economies, already devalued its currency, the tenge, last April by 19%. But now it faces another devaluation with the rouble dropping 30%. The Kazakh government also slashed its growth estimates last month.

Putin may have weakened the ability of the neoliberal, pro-EU leaders in Kiev to join ‘Europe’ so Ukraine will remain an economic disaster, but, in turn, American and European imperialism is inflicting significant economic pain on Russia.

No comments:

Post a Comment