Last week I spoke on a panel that debated De-industrialisation and socialism. The panel was organised by Spring, a Manchester-based group in England that has become a forum for the discussion of developments in capitalism and their implications for the prospects for socialism (http://www.manchesterspring.org.uk/).

The main theme for this panel discussion was the evident fact that the industrial sector (manufacturing, mining, energy etc) has declined sharply as share of the output and employment in the mature capitalist economies during the 20th century. The question for debate was: does this mean that the working class has also declined and is no longer the main force of change in capitalism; and also that a socialist or post-capitalist society will be a world without industry or employment of industrial workers?

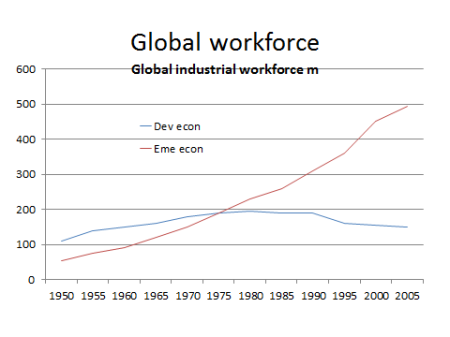

The first point I made in the discussion was that the world is not de-industrialising. Globally, there were 2.2bn people at work and producing value back in 1991. Now there are 3.2bn. The global workforce has risen by 1bn in the last 20 years. But there has been no de-industrialisation globally. De-industrialisation is a phenomenon of the mature capitalist economies. It is not one of the ‘emerging’ less developed capitalist economies.

Using the figures provided by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) we can see what is happening globally, with the caveat that there is a serious underestimate of industrial workers in these figures and such transport, communication and many hi-tech workers are put in the services sector.

Globally, the industrial workforce has risen by 46% since 1991 from 490m to 715m in 2012 and will reach well over 800m before the end of the decade. Indeed, the industrial workforce has grown by 1.8% a year since 1991 and since 2004 by 2.7% a year (up to 2012), which is now a faster rate of growth than the services sector (2.6% a year)! Globally, the share of industrial workers in the total workforce has risen slightly from 22% to 23%. It is in the so-called mature developed capitalist economies where there has been de-industrialisation. The industrial workforce there has fallen from 130m in 1991 by 18% to 107m in 2012.

The big fall has not been in industrial workers globally but in agricultural workers. The process of capitalism sucking up peasants and agro labourers from the rural areas and turning them into industrial workers in the cities is not over. The share of agricultural labour force in the total global workforce has fallen from 44% to 32%. So should we not really talk about de-ruralisation, as Marx did in the mid-1800s? That is the great global phenemonon of the last 150 years.

Of course, most workers globally work in the services sector. This sector is badly defined, as I say, and is really anybody not clearly an industrial or agricultural worker. This sector was smaller than agriculture in 1991 (34% to 44%) but now it is biggest at 45% compared to 32% for agriculture.

As I was speaking in Manchester, the centre of the industrial revolution in Britain in the early 19th century, I was reminded of the work of Friedrich Engels, Marx’s partner in crime, who was managing his uncle’s German firm in the city at the time. As a young man (29 years), Engels wrote The condition of the working-class in England in 1844

(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Condition_of_the_Working_Class_in_England)

and described the horrendous conditions of squalor, disease, sweat shop conditions, injury and poverty that rural men, women and children were subjected to as they came to work in the fast industrialising and urbanising cities of northern England. It’s the same story now in the likes of India, China, south-east Asia and Latin America. Engels concentrated on the conditions for labour, but in a preface to a new edition of his book in 1892, he commented that Britain was fast being replaced as the major industrial capitalist power by France, Germany and the US. “Their manufactures are young as compared with those of England, but increasing at a far more rapid rate than the latter. They have reached the same phase of development as English manufacture in 1844”. And so it is now for the so-called emerging economies of Asia, Latin America and Africa compared to the mature capitalist economies of Europe, Japan and North America.

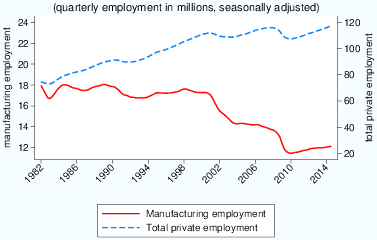

But it’s true that the share of industrial workers in the mature economies has fallen from 31% in 1991 to 22% now. Indeed, according to McKinsey, manufacturing employment fell 24% in the advanced economies between 1995 and 2005.

So does this mean that the future of capitalism without an industrial proletariat capable of being an agency for change and, for that matter, ‘post-capitalism’ will a society without industry, where people can expect to reduce their hours of work for a living and have increased periods of ‘leisure’?

This was the theme that my fellow panellist Nick Srnicek posed. Nick is a Fellow in Globalisation and Geopolitics at UCL. He is the author with Alex Williams of Inventing the Future (Verso, 2015) and the editor with Levi Bryant and Graham Harman of The Speculative Turn (Re.press, 2010) – see

http://criticallegalthinking.com/2013/05/14/accelerate-manifesto-for-an-accelerationist-politics/).

Nick explained that, while new economies were being industrialised, their peak of industrialisation came earlier than for economies like Britain in the 19th century. Indeed, no economy had achieved more than a 45% share for industrial employment. So the future is not industry and an industrial working-class. And it was no good advocating a return to manufacturing and industry as the way forward for a better society.

I am sure that Nick is right in these points. Where I differed was that he was not clear if a post-capitalist, non-industrial society would be achieved gradually as capitalism expanded globally and technology replaced heavy industrial work and people worked less hours and could use their time for themselves. The idea of a steady move to a post-industrial, leisure society was the concept of Keynes back in the 1930s, arguing for capitalism as the way forward to his students at the height of the Great Depression in the 1930s, when many of his students had started to look to Marxism as the explanation for crises and the alternative of socialism (see my post, http://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2013/05/04/keynes-being-gay-and-caring-for-the-future-of-our-grandchildren/ ).

Keynes reckoned the capitalist world would achieve huge per capita GDP growth and enter a ‘post-capitalist’ leisure economy without poverty. Well, this blog has regularly revealed data that show poverty remains a terrible spectre over the globe, an inherent feature of capitalism, and that far from moving to a leisure society, working hours have hardly fallen much in the mature economies and remain very high in industrial sectors of the emerging economies. We are all still ‘toiling’ for a living (apart from the 1%), in increasingly precarious jobs.

I don’t think we can get a ‘post-capitalist’ leisure society through gradual change. It will require a revolutionary upsurge to change the mode of production and social relations globally, even if the potential productivity of labour through new technology and robots etc is already there globally to deliver such a transition to freedom from toil. Capitalism remains in the way as a fetter on production, with capitalists as a class force opposed to freedom.

The reason that the mature capitalist economies have lost their industrial base is that it was no longer profitable for capital to invest in British industry in the late 19th century or OECD industry in the late 20th century. So capital counteracted this falling profitability by ‘globalising’ and searching for more labour to exploit.

And profitability fell because capitalist accumulation is labour-shedding. Capitalists compete against each other to get more profit. Those capitalists with better technology can steal a march on others by boosting labour productivity and reducing labour costs by cutting the workforce. So the drive is always for reducing the amount of labour power to boost profits. The central contradiction here, as explained by Marx’s law of profitability, is that the reduction in labour power relative to mechanisation leads to an eventual fall in profitability. This reduces the industrial workforce in the mature economies and leads to expansion of industry globally. Capitalism is a mode of production for mechanisation, but mechanisation will also lead to its demise as it is a mode of production for profit not social need and more mechanisation eventually means less profitability. That shows that as we move towards a robot economy: profit for capital and meeting social needs will become more incompatible. And the leisure society just an impossible dream.

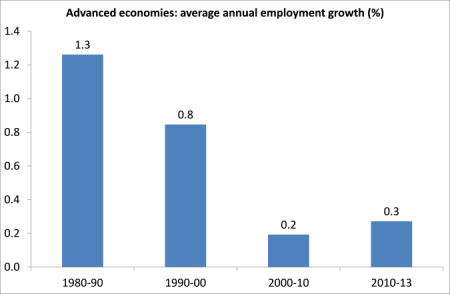

Employment growth is falling in the advanced capitalist economies. Employment growth is way less than 1% a year in the 21st century.

Computer engineer and Silicon Valley software entrepreneur, Martin Ford puts it this way: “over time, as technology advances, industries become more capital intensive and less labour intensive. And technology can create new industries and these are nearly always capital intensive”. The struggle between capital and labour is thus intensified.

It does depend on the class struggle between labour and capital over the appropriation of the value created by the productivity of labour. And clearly labour has been losing that battle, particularly in recent decades, under the pressure of anti-trade union laws, ending of employment protection and tenure, the reduction of benefits, a growing reserve army of unemployed and underemployed and through the globalisation of manufacturing.

According to the ILO report, in 16 developed economies, labour took a 75% share of national income in the mid-1970s, but this dropped to 65% in the years just before the economic crisis. It rose in 2008 and 2009 – but only because national income itself shrank in those years – before resuming its downward course. Even in China, where wages have tripled over the past decade, workers’ share of the national income has gone down. Indeed, this is exactly what Marx meant by the ‘immiseration of the working class’.

Will it be different with robots? Marxist economics would say no: for two key reasons. First, Marxist economic theory starts from the undeniable fact that only when human beings do any work or perform labour is anything or service produced, apart from that provided by natural resources (and even then that has to be found and used). So, crucially, only labour can create value under capitalism. And value is specific to capitalism. Sure, living labour can create things and do services (what Marx called use values). But value is the substance of the capitalist mode of producing things. Capital (the owners) controls the means of production created by labour and will only put them to use in order to appropriate value created by labour. Capital does not create value itself.

Now if the whole world of technology, consumer products and services could reproduce itself without living labour going to work and could do so through robots, then things and services would be produced, but the creation of value (in particular, profit or surplus value) would not. As Martin Ford puts it: the more machines begin to run themselves, the value that the average worker adds begins to decline.” So accumulation under capitalism would cease well before that robots took over fully, because profitability would disappear under the weight of ‘capital-bias’. This contradiction cannot be resolved under capitalism.

We would never get to a robotic society; we would never get to a workless leisure society – not under capitalism. Crises and social explosions would intervene well before that.

No comments:

Post a Comment